Mirka didn’t move far from the Tolarno. She rented a shopfront and dwelling at 26 Wellington Street, off St Kilda Junction and about a ten minute walk. ‘Everybody visits me’, she said. It seemed Mirka was continuing the same open house policy she and Georges had adopted since 9 Collins Street. Fashion designer Jenny Kee and her partner artist Michael Ramsden came to stay, as did journalist Mary Craig and the poet Michael Dransfield. Jean Shrimpton dropped in. But there were rules. Mirka worked solidly from 9am until 2pm, when no visitors were allowed. Then after a bath - ‘I get covered in paint’ - she had lunch, often at a nearby restaurant or cafe, and connected with family and friends.

Mirka didn’t move far from the Tolarno. She rented a shopfront and dwelling at 26 Wellington Street, off St Kilda Junction and about a ten minute walk. (50) ‘Everybody visits me’, she said. (51) It seemed Mirka was continuing the same open house policy she and Georges had adopted since 9 Collins Street. Fashion designer Jenny Kee and her partner artist Michael Ramsden came to stay, as did journalist Mary Craig and the poet Michael Dransfield. Jean Shrimpton dropped in. But there were rules. Mirka worked solidly from 9am until 2pm, when no visitors were allowed. Then after a bath - ‘I get covered in paint’ - she had lunch, often at a nearby restaurant or cafe, and connected with family and friends. (52)

I first met Mirka in 1974 when I was an art history student at Melbourne University. I was organising a feature on women artists for Farrago, the student newspaper, of which I’d been appointed art critic. Mirka was one of the first woman artists I had met. Apart from being astonished by the Aladdin’s cave at Wellington Street, there was Mirka herself: disarming, witty, intense and unique. She’d abandoned her chic French style for a vintage look. A typical outfit would be a sweeping velvet dress adorned with lace collar and cuffs, child’s red shoes, her long dark hair worn loose, her eyes outlined with kohl - fashion statements from the hippie era. But it was a style that suited her environment: most of the objects Mirka collected belonged to earlier eras. There was little that was modern at Wellington Street.

I asked if she felt discriminated against as a woman artist. ‘I’d say I wasn’t taken seriously first because I had three children’. Did she think having children meant some women artists dropped out? ‘Yes. They are not maniacs like I am. They haven’t got the feel for learning more or something’. (53) Her confidence as a woman artist was unusual for the time. When Barrett Reid asked her if she felt unappreciated, Mirka replied, ‘No, because I have such confidence in my work and I know my work is quite something’. (54) I would be hard put to think of another Melbourne woman artist who, at that time, would speak so boldly.

Mirka was a true collector – enough was never enough. Over the years, she continued to acquire vintage toys, prams, fine china, exquisite pieces of fabric, books, both antiquarian and recent, records (usually of classical music), clothes that might be from an op shop or carry a designer label, handbags, shoes, hats, furniture, sewing machines, easels, palettes, paints and brushes. Even a piano. She bid by phone at international auctions for some particular item she desired, meaning her bank balance often suffered.

This gorgeous clutter occupied the entirety of her home/studio, the mass of objects becoming an artwork in its own right, a labyrinth of treasures, a trove of visual and tactile delights, a catalogue of her obsessions, a mirror of her personality. Many visitors recall the experience of edging sideways down the hall because there was scarcely room to move. As Sabine Cotte comments, ‘To have a cup of coffee at Mirka’s, you had to physically move some things from the table and from a chair in order to lay down your cup and have a seat’. (55) After ensconcing myself in my gracious 1920s St Kilda apartment, I said to Mirka, ‘You know, I think I’m becoming house proud’. She was aghast. ‘You are a writer! You cannot become house proud!’

Wellington Street was quite a dark space – like all Mirka’s domiciles. She was not an artist who craved sunshine and vistas. Visiting her at Wellington Street and later at her home at Barkly Street, was to enter a shadowy, atmospheric zone where strange and rare objects could be glimpsed. Where layers of dust were thick. Where silence dominated. Where the blank gaze of dolls and the staring eyes of teddy bears could seem macabre and eerie. All was not cheerful in that place. There were sinister resonances, like the dark side of fairy tales, that promise not safety but fear, alerting the reader to the threats and dangers that can be endemic to magical realms. Be wary! Take care! Myths contain lessons and truths learned at one’s peril. Such allusions, too, were contained in Mirka’s world, offering a contrast with the breezy vitality of her presence. Her home/studio was a tableau vivant and she shone brilliantly in its twilight.

There was one window left open. That was for Pompom, her hefty, male tabby cat. ‘Look at his beautiful balls, Zhaneen!’, Mirka exclaimed. ‘He shouldn’t have balls, Mirka’, I answered crossly. ‘He’s impregnating local cats’. She looked startled. ‘But he is a man!’

In retrospect, I wonder, did Mirka contrive to establish a space – after the shock of leaving her family, after the enormous gap that created – which banished emptiness? Was it a kind of horror vacui? Or did the darkness function as a deep creative zone, a kind of womb-like territory, the original and fecund place of fertility, growth and birth, both literally and symbolically? Mirka was also thoroughly committed to the power of the unconscious mind, that fertile territory whose chief archaeologist was Sigmund Freud who alerted us that our dreams carried complex messages – about sexuality and family - that required analysis to decode.

‘When all is said and done’, Mirka reflected,‘it is still difficult to know how and when a good painting comes. A while ago I heard that a pig has the intelligence of a child of five years old. A lovely painting arrived (Mirka means she created it) with a child and an angel holding a pig. I was very pleased with this painting’. (56) It had arrived from the matrix of her unconscious mind. Though more than one journalist, surrounded in the studio by Mirka’s images and Mirka herself, noted the insistent focus on self that could be read from the ‘sloe-eyed figures in her paintings, to glamorous studio shots from her bohemian youth’. (57) Mirka would not be the first artist to take her own face as subject matter. Frida Kahlo’s oeuvre prized her distinctive physical features. Perhaps the plenitude of such images indicates, on the part of the artist, a constant interrogation of identity and its visceral manifestations.

Amid the turmoil of leaving her husband and her sons (Philippe was studying film in London), and settling in her own home, a fresh burst of inspiration carried Mirka forward. She began to make soft sculptures – dolls. At first, Mirka was unable to draw. ‘As a rule’, Mirka reflected, ‘I do not paint if I am distressed, I like to have a clear mind. I was extremely distressed, and brave, when I left my family’. She found herself ‘cutting out my drawings, and they looked like the paper dolls I used to play with as a child...The dolls were a kind of solid dream: I was enthralled by them’. (58) Did the dolls also represent her ‘lost’ sons, giving her permission to hold and keep them in a way that was not possible in reality? A reality she had brought into being?

To make the dolls Mirka took bedsheets and pillow cases - never new, always used and often begged from friends – which she then machine-sewed, stuffed and painted. The textures of much-washed linen was an inherent part of the doll-making process. ‘I only wanted to work on the bedsheets or pillowcases. It had to be dreams, where people slept on...I remember a lady with about seven children gave me some...from all her little boys’. It was ‘most inspiring and of course to paint on bed clothes is lovely because the material has been washed a lot’. (59)

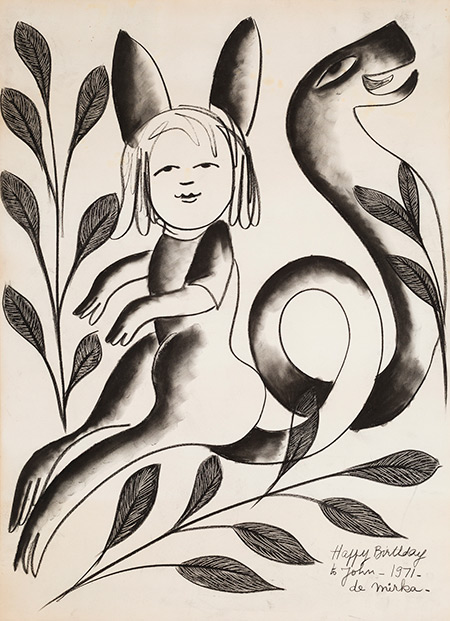

The dolls proved very popular. In 1971, Mirka exhibited them at Marianne Bailleu’s prestigious Realities Gallery in Toorak. John Reed wrote an introduction. The dolls sold well and earned praise. But Mirka was averse to churning out more merely to make money. ‘I could have made a fortune, as people adored (the dolls)...but I thought it was too good a pleasure for one person and decided to do workshops, sharing my knowledge with people’. (60)

Mirka began to run doll-making workshops that took her through rural Victoria and NSW. Not only did the classes earn some cash but they spread the joy and pleasure that doll-making gave. She also co-ordinated the completion of murals in a variety of public places. Mirka was a natural teacher –astute, organised, encouraging.

Jenny Kee was grateful for Mirka’s mentoring. While staying with Mirka, she encouraged Kee to make a doll. Mirka ‘wanted to coax the artist out of me’, Kee recalls. The process was inspiring. ‘My doll was a totem, symbolising my transformation into an artist’. (61) In 1973, Kee started Flamingo Park, an innovative fashion boutique in Sydney, with fellow fashionista Linda Jackson.

Mirka took her role as an educator very seriously, believing that anyone could be an artist. Mirka herself was the example: she had no art training prior to becoming a painter. Mirka enjoyed the sense of community that teaching offered and it’s one reason why she gained such popularity, making the mourning of her death in 2018 a very public event in Melbourne.

Mirka had a strong extroverted streak. New friends, gossip, hi-jinks, dramas, shared experiences and long lunches washed down with plenty of wine, were as necessary as the quiet times in the studio. Not that Mirka over imbibed. Chateau d’Yquem, a dessert wine, was a favourite. Today a bottle could set you back five hundred dollars. Mirka kept a box of it under her bed. Once I asked her about her relationship with alcohol. She said – fervently - ‘I am afraid of it’. Given that two of her dearest and most talented friends – Charles Blackman and John Perceval - virtually destroyed themselves with drink makes explicable her attitude.

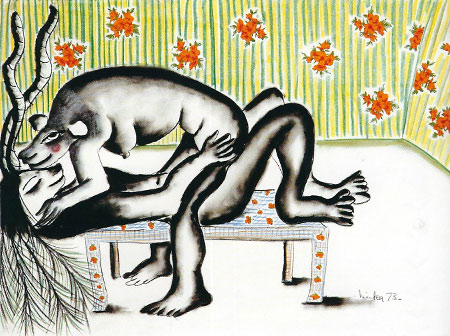

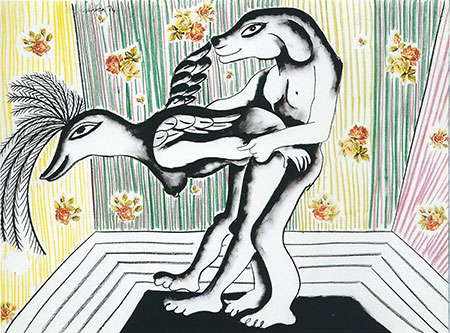

In 1973, Mirka began a daring new series - erotic drawings boldly sketched in charcoal. While today images such as the smiling bestial lovers in The Grizzly Bear is Huge and Wild (1973, Private Collection) seem merely tender and amusing, at the time they were quite scandalous – especially from a woman artist. It’s interesting to observe how, despite the sudden rush of activity by women artists in the early to mid-1970s, few committed themselves to sexual iconography. When they did it was often critical such as Ann Newmarch’s series of prints Suburban Reflections (1973) where images of naked women gleaned from advertisements were contrasted with gruesome photographs from the Vietnam War.

While Joy Hester’s 1955-56 Lovers series, showed the coupling between a man and a woman as having a violent, claustrophobic quality, Mirka displayed intercourse as gentle and playful, and mutually enjoyable. The lovers are part-animal, part-human but delightfully so. Perhaps another resonance from the happiness she experienced with Ross? Once Mirka showed me photographs of her first lovemaking experience with Ross on a trip to Sydney. Mirka looked very fetching in black lacy bra and knickers. I was slightly taken aback. Once you knew Mirka, you realised she did not often keep secrets. She liked to shock but, equally, she liked to tell the truth. Her truth.

In 1975, the business-friendship with Marianne Baillieu enticed Mirka to move next door to the gallery’s new premises in a renovated church hall in Jackson Street, Toorak. Mirka lived in the cottage which had served as the vicarage. When the relationship with Marianne soured, Mirka shifted to Rankins Lane, off Little Bourke Street, in the CBD. The 1970s were a time when many artists were reclaiming the city as an artists’ space and they moved into the lofts in its maze of lanes.

It was a nice reminder for Mirka that in the 1950s she and Georges had spearheaded a return to the city as a cultural zone. It had been a milieu that Melbourne artists had enjoyed since the 19th century up until World War II. In the 1930s and 40s, its denizens had included Sam Atyeo, Sidney Nolan, Noel Counihan, Tucker and Hester, as well as a plenitude of galleries, bookshops and cafes.

Mirka told me she left Toorak because she felt under pressure from Marianne who wished her to show more often. Mirka was rigorous about how regularly she exhibited. To have too many exhibitions was to diminish one’s focus and integrity. She was also very attached to her work – especially the dolls – and did not wish to part with them. Living close to Realities also meant various celebrities and visitors would be taken across to Mirka’s, interrupting her work rhythm. (I must confess that I often dropped by. I’d call out, ‘Mirka! If you’re working, tell me to go away!’ She never did.)

See more of the Mirka Mora Project

Credits

{slider-ex title="Author" open="false" class="icon"}

Dr Janine Burke is an author, art historian and a local resident for thirty-five years. She is Honorary Senior Fellow, University of Melbourne and committee member, St Kilda Historical Society.

{slider-ex title="Notes" class="icon"}

{slider title="From Paris to Melbourne" open="false"}

- Albert Tucker to Sunday Reed. 31 January, 1951. John and Sunday Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria.

- Albert Tucker to John and Sunday Reed. 27 August, 1950. John and Sunday Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria.

- Mirka Mora, Wicked but Virtuous: My Life, Viking, Ringwood, 2000, p.13.

- Pithiviers station is undergoing transformation as a Holocaust museum. See Melian Solly. ‘Museum to be built at Site of Nazi Occupied France’s First Concentration Camp’, December 18, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/museum-built-site-nazi-occupied-frances-first-concentration-camp-set-open-2020-180971126/ Accessed 1 July 2019.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.15.

- Zelda Cawthorne, ‘Treasure Trove of Mirka’, 18 June, 2014. https://www.jewishnews.net.au/treasure-trove-from-mirka/35684 Accessed 2 July 2019.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.15.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.20.

- Lesley Alway and Kendrah Morgan, Mirka and Georges, A Culinary Affair, The Miegunyah Press, Heide Musuem of Modern Art, 2018, p. 21.

- For a description of the history and activities of the Oeuvre de secours aux enfants see https://www.ose-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Bochure-100-ans-OSE-anglais.pdf Accessed 4 January 2020.

- Georges’ heroic activities in OSE are described in Monsieur Mayonnaise (2016). Documentary film. Philippe Mora, narrator. Trevor Graham, writer and director. Trevor Graham, Ned Lander and Lisa Wang producers, Antidote Films.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.40.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.25.

- Quoted in Dianne Reilly, ‘Antoine Fauchery, 1823–1861 Photographer and Journalist Par Excellence’, La Trobe Journal, no 33, April 1984, p.3, fn 9. http://www3.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-33/t1-g-t1.html. Accessed 3 July 2019. While following cash and adventure to Japan, Fauchery died in Yokohama in 1861, due to complications from dysentery. He was 37.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.159.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.48.

{slider title="Paris End of Collins Street - 1950s"}

- G.R. Lansell, Email to the author, 15 June 2019.

- In 1992, Mirka travelled to France to teach a workshop titled Adventure in Art: Mirka en Provence which included a stint at Saint-Paul-de-Vence on the French Riviera. Organised by John and Shirley Traynor, it took place shortly after Georges died. The group spent time in Paris, Mirka noting, ‘of course [the tour] included almost all the places I had been with my husband’. Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.219. In 1994, Mirka travelled to France when Philippe Mora, based in Los Angeles, invited her to attend the Cannes film festival with him.

{slider title="St Kilda, Fitzroy Street (Tolarno) 1966-1970"}

- Jackie Somerville. Telephone interview with the author. 22 May 2020.

- Judith Buckrich, Acland Street, The Grand Lady of St Kilda, Australian Teachers of Media, St Kilda, 2017, p. 110.

- Buckrich, Acland Street, p.101.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p. 85.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.87. The original 1966 mural is in the collection of Heide Museum of Modern Art.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.86. The room which Mirka first occupied on the ground floor as her studio was appropriated by Georges for Tolarno Gallery, so Mirka moved into the basement where she had three rooms. On the first floor, she had a bedroom separate from Georges which also served as a smaller studio.

- Richard Peterson, ‘Tolarno Hotel’, in A Place of Sensuous Resort. St Kilda Buildings and Their People, Chapter 17, p.5. http://www.richardpeterson.com.au/a-place-of-sensuous-resort. Accessed 4 July 2019.

- For an overview of the history of the Tolarno from its building to the 1970s see Peterson, A Place of Sensuous Resort. Chapter 17, pp.5-8. http://www.richardpeterson.com.au/a-place-of-sensuous-resort.

- Tricia Goodwin, ‘Love Among the Ruins’, The Herald, 28 November, 1968, p.21.

- It’s unlikely Mirka read Death at the End of the World available in the original French edition. If she had, she would have known that Lionel and Céleste’s home was a five room ‘chalet...made of pine with a galvanised-iron roof’ in St Kilda. Patricia Clancy and Jeanne Allen, Introduction and translation, The French Consul’s Wife, Memoirs of Céleste de Chabrillan in Gold-rush Australia, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 1998, p.113.

- ‘We have found some land two leagues (around 10 kilometres) from the town in the heart of the woods, near a village called Saint-Kilda (sic). We are going to erect the house that I bought in Bordeaux on this site’. Clancy and Allen, The French Consul’s Wife, p.95.

- Clancy and Allen, The French Consul’s Wife, p.95.

- Fauchery’s letter, dated 4 February 1859, is quoted in full in Clancy and Allen, The French Consul’s Wife, pp.237-242.

- Mirka Mora to Sunday Reed. 10 March 1967. John and Sunday Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria. MS 13186. 2.20. Mirka Mora Correspondence.

- Sweeney Reed (1945-1979) was the adopted son of John and Sunday Reed. Sweeney was the son of the marriage of Joy Hester and Albert Tucker. In 1967, Sweeney was director of Strines, a gallery in Carlton.

- G.R. Lansell. Email to the author, 16 December 2019.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, pp. 165-166.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.169.

- Bernard Smith, Australian Painting, Oxford University Press, London, 1971, p. 312.

- Janine Burke ‘Donald Laycock’, Art and Australia, October – December 1975, Vol 13, No 2, pp. 144-151.

- G.R. Lansell. Email to the author, 16 December 2019.

- Georges Mora to Sunday Reed. 27 December 1970. John and Sunday Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria. MS 13186, Box 2/18, File 7.

- Mora to Reed. 27 December 1970. John and Sunday Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria. MS 13186, Box 2/18, File 7.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, pp.166-167.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.163.

- G.R. Lansell. Email to the author, 16 December 2019.

- Mora’s scrapbook is in the collection of Heide Museum of Modern Art.

- Sheila Sibley, ‘And art was her choice’, Sunday Observer, 21 June, 1970. Interestingly, Mirka included the same anecdote in her autobiography Wicked but Virtuous: My Life (2000) indicating the potency of Chevalier’s question and her answer. See Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.77.

- Keith Dunstan, ‘A Place in the Sun’, The Sun, 4 June 1971.

- Janine Burke (ed), Dear Sun: the letters of Joy Hester and Sunday Reed, William Heinemann Australia, Melbourne 1995, p.203.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.54.

{slider title="St Kilda, Wellington Street 1970-1975"}

- The shopfront-dwelling at 26 Wellington Street was demolished to make way for a block of units.

- Sheila Sibley, ‘And art was her choice’, Sunday Observer, June 21, 1970.

- Sheila Sibley, ‘And art was her choice’, Sunday Observer, June 21, 1970.

- Janine Burke and Lynne Cook, ‘Mirka Mora’, Farrago, April 26, 1974, p.11.

- Transcript of interview with Mirka Mora by Barrett Reid, 14 January 1971, p.21. Barrett Reid Papers, State Library of Victoria. MS 13339, Box 9, File 2, Wallet 1/1.

- Sabine Cotte, Mirka Mora: A life making art, Thames and Hudson, Melbourne, 2019, p. 80.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.156.

- Jane Freeman, ‘Mora’s magic in full bloom’, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 September, 1996, p.14.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, pp. 147-148.

- Burke and Cook, ‘Mirka Mora’, Farrago, p.11.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p. 148.

- Jenny Kee with Samantha Trenoweth, A Big Life, Lantern, Melbourne, p.132.

{slider title="St Kilda, Barkly Street 1981-1999 and beyond"}

- Mirka Mora to Janine Burke, 2 November 1981. Mirka Mora Papers. Box 3, Correspondence. Brown Envelope 11. Heide Museum of Modern Art.

- William Mora. Telephone conversation with the author. 6 November 2019.

- Mora to Burke, 2 November 1981. Mirka Mora Papers, Box 3, Correspondence. Brown Envelope 11. Heide Museum of Modern Art.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, pp.53-54.

- Bridie Carter. Email to the author. April 16, 2019.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.299.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.300.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.300.

- Rachel Berger, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, Issue 81, October-November 2018, p. 21.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p. 149.

- Helen Halliday, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, Issue 81, October-November 2018, p.19.

- Halliday, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, p.19.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p. 152.

- Ann Holt, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, Issue 81, October-November 2018, p.16.

- Gail Donovan, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, Issue 81, October-November 2018, p.18.

- Donovan, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, p.18.

- Ross Lansell remembers it rather differently. ‘Gail and Kevin very generously provided us two with a late impromptu Christmas lunch for free (also from memory, not exactly for the first time). I remember shortly thereafter personally delivering to Gail and Kevin (Mirka wasn’t present) a modest gouache...to thank them’. G.R.Lansell. Email to the author. October 31, 2019.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.242.

- Cotte, Mirka Mora: A life making art, p.177. Cotte was also responsible for the conservation of Mora’s Flinders Street Station mosaic. She worked on it in March 2009, then again in November 2010.

- Cotte, Mirka Mora: A life making art, p.177.

- Cotte, Mirka Mora: A life making art, p.177.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.243.

- Tolarno Gallery is now at Level 4, 101 Exhibition Street, Melbourne (at time of writing) and its director is Jan Minchin who joined Georges as assistant director in the late 1970s.

- Guy Grossi, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, Issue 81, October-November 2018, p.18.

- G.R.Lansell. Email to the author. 16 December 2019.

- Serge Thomann. Email to the author. 6 November 2019.

- Serge Thomann. Email to the author. 6 November 2019.

- Jane Touzeau. Email to the author. 5 January 2020.

{slider title="Epilogue"}

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, pp. 299-302.

{/sliders-ex}

{/sliders}